Women in the history of University of Hamburg

Each month during Universität Hamburg’s 100th anniversary celebrations, the Equal Opportunity Unit will publish a short biography of one of the women who paved the way for other women in research, teaching, and studies at Universität Hamburg.

December: Gabriele Löschper

Picture: dpa/DPA/A9999 Tobias Kleinschmidt

Prof. Dr. Gabriele Löschper, a social psychologist and criminologist, was the first full-time equal opportunity commissioner at Universität Hamburg and vice president of Universität Hamburg and has served as the dean of the Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences since 2010.

Gabriele Löschper was born in December 1954 in Lüdenscheid. After she finished her schooling, she studied psychology at the University of Münster, graduating in 1978 with a Diplom. She went on to gain her PhD in 1981 at the same university with her doctoral dissertation “Definitionskriterien aggressiver Interaktionen. Normabweichung, Intention und Schaden als Einflussfaktoren auf die Definition von Verhaltensweisen als aggressiv” (Definition criteria of aggressive interactions. Deviation from the norm, intention, and damage as factors influencing the definition of behavior as aggressive) Following her time at Münster, she moved to Universität Hamburg in 1984 to work as a research associate in the criminology graduate degree program and Open Study Program in the former Department of Law. From 1993 to 1995, Löschper was the recipient of a Habilitation scholarship from the German Research Foundation. Then from October 1996 to September 1997, she completed her postdoctoral qualification at the University of Bremen in the faculty Human and Health Sciences with her Habilitation thesis “Bausteine für eine psychologische Theorie richterlichen Urteilens” (Building blocks for a psychological theory of judicial judgment). The University of Bremen authorized her to teach social psychology and criminology. Until 2002, Löschper worked at the Institute of Criminological Social Research in the Department of Social Sciences at Universität Hamburg and was the women’s affairs commissioner from 2001 to 2002. A year later Universität Hamburg appointed her a professor as defined in Section 17 of the Hamburg higher education act (Hamburgisches Hochschulgesetz, HmbHG).

In 2002, Gabriele Löschper was elected the first full-time equal opportunity commissioner of Universität Hamburg. Up to that point, this task had been carried out on a part-time basis only. Löschper was urged to apply for the position of full-time equal opportunity commissioner at Universität Hamburg by colleagues from various fields whom she knew from her previous involvement in different committees (e.g., as spokesperson of the group of university assistants / research associates in the Academic Senate) and who admired her ability to clearly identify issues and positions and argue them calmly but steadfastly. Löschper herself cites humor and self-deprecation as important requirements to work successfully and satisfyingly as an equal opportunity commissioner (or vice president or dean). In her role as full-time equal opportunity commissioner, she said it was crucial to make equal opportunity a subject matter for women and men and to show that improvements for women at the University can lead to improvements of the University and its structures in general.

During Löschper’s term of office, many structures and processes for the promotion of equal opportunity at Universität Hamburg were established or expanded. As equal opportunity commissioner, she oversaw—inter alia—the setup and development of the former Women’s Career Center at Universität Hamburg. She held the office of equal opportunity commissioner for 5 years in total.

From 2004 to 2007, Gabriele Löschper was a member of the University Council of Universität Hamburg (as one of two members selected by Universität Hamburg).

Following her term of office as equal opportunity commissioner, she was elected vice president for organizational structure and HR development of academic staff in 2007. In this role, she had a key hand in the drafting of the University’s first Structure and Development Plan and developed (along with Manfred Nettekoven, Universität Hamburg’s former head of administration) an HR development program for junior professors and early career research group heads.

From July 2009 to February 2010, Löschper headed Universität Hamburg on an interim basis as acting vice president following the termination of Prof. Dr. Monika Auweter-Kurtz’s contract as president of Universität Hamburg.

Since May 2010, Gabriele Löschper has been the full-time dean of the Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences. According to Löschper, it is a big advantage to have been able to experience the University in many different functions and roles (as an academic in various departments/faculties, a member of committees, the equal opportunity commissioner, a University Council member, vice president, dean). It has allowed her to look at the situation and development of the University from very different perspectives and university cultures.

Research

In her research, Löschper focused on criminology, sociology of criminal law, forensic psychology, judicial judgments, and violence and played a key role in shaping the specialist discipline of criminology at Universität Hamburg.

With the publication of the text collection Das Patriarchat und die Kriminologie (2000), Löschper also focused on entrenching the question of gender in criminological discourse and advancing critical and feminist criminology. Until 2003, she was also chair of the Gesellschaft für Interdisziplinäre Wissenschaftliche Kriminologie.

Commitment to equal opportunities

During her time as equal opportunity commissioner for Universität Hamburg, she introduced—among other things—the Women’s Advancement Fund, which provides funding for the promotion of projects to dismantle gender-related disadvantages in studies, teaching, research, and administration.

A further step for equal opportunities was the research project “Frauen in der Spitzenforschung,” which looked at women in top-level research and was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) from 2008 to 2013. Löschper (along with Prof. Dr. Ulrike Beisiegel, formerly at the Faculty of Medicine at Universität Hamburg) initiated the design of this project. Under the leadership of Prof. Dr. Anita Engels (Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences), the project examined the extent to which the Excellence Initiative of the Federal and State Governments implements equal opportunities for men and women. It concentrated on the issue of underrepresentation of women in university research, with the goal of supporting the nationwide expansion of structures that promote women in top-level research.

Löschper believes that it is now far more natural to talk about equal opportunity issues and diversity measures than it was during her time as the women’s affairs commissioner and, later, as the equal opportunity commissioner. The Excellence Strategy, previously the Excellence Initiative, has likely contributed to this, within whose framework all applicant universities in the various funding lines have been repeatedly urged to make greater efforts to increase the proportion of women, especially in the top positions of collaborative projects.

Gabriele Löschper also represents the issue of equal opportunity in her current role as dean of the Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences. This is why so many members of the University value Löschper’s advice with regard to equal opportunity questions, strategic considerations, dealing with problems, and decisions to be taken. Löschper explains that it sometimes requires a lot of energy for women in university management to deal with the fact that they are considered less strategically competent, less efficient, and less assertive. She advises not giving up, tenaciously pursuing one’s own goals, and growing a thicker skin. Even in critical situations and conflicts, it is important to argue and appear firm and authoritative.

Following her term of office as dean of the Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences, Löschper plans to return to her criminology roots—namely, to extensively read crime novels.

Gabriele Löschper during her laudation at the awarding of the Equal Opportunity Prize 2019 to the Career Center team at Universität Hamburg (Picture: UHH/Saint Pere)

Further information and literature

Women’s Advancement Fund

https://www.uni-hamburg.de/en/gleichstellung/foerderungen/frauenfoerderfonds.html

Research project “Frauen in der Spitzenforschung”

https://www.campus.de/e-books/wissenschaft/soziologie/bestenauswahl_und_ungleichheit-10104.html

November: Martha Muchow

Source: Martha Muchow Library

Martha Muchow was an instructor and postdoctoral psychologist at Universität Hamburg, where she play a key role in the development of the university teacher training degree program. She committed suicide as a result of the repressions she faced under National Socialism.

Martha Marie Muchow was born on 25 September 1892 in Hamburg as the daughter of a customs inspector. After earning her Abitur (German secondary school leaving certificate) in 1912, she became a teacher and spent two and a half years working at a secondary school for girls in Tondern, Denmark. From 1915, she then taught at public schools in Hamburg. In her free time, she attended lectures in the General Lecture Series at the Psychological Laboratory, a department of the philosophy seminar, which was a predecessor institution to Universität Hamburg. During this time, Martha Muchow already published her first academic papers and worked on tasks in the laboratory in addition to teaching. This was how she first came into contact with the well-known Professor William Stern, who became the head of the laboratory in 1916 and would have a pivotal influence on Muchow’s life.

When Universität Hamburg was founded in 1919, Martha Muchow was one of the first female students of psychology, philosophy, German philology, and literary history. From 1920 she took a leave of absence from teaching, with the support of William Stern, in order to work as a research assistant at the Psychological Laboratory. In 1923 earned her doctorate with the grade summa cum laude with a dissertation on “Studien zur Psychologie des Erziehers“ (studies on the psychology of the educator). Martha Muchow was appointed an academic councilor at the Institute of Psychology of Universität Hamburg in 1930.

When the National Socialists assumed power, Martha Muchow immediately began facing both personal and professional struggles. She was worried about the restrictions placed on teaching and researching freedom as well as about political developments as a whole. The Institute of Psychology at Universität Hamburg where she worked at that time was defamed by the National Socialists as a “Jewish institute” and therefore instructed to adapt to National Socialist philosophy as quickly as possible. Muchow’s closest confidant and head of the institute, William Stern, was banned from his profession due to his Jewish heritage in April 1933. Following this development, Muchow effectively became the head of the institute and was expected to prepare it for handover to the National Socialists as she was the only “non-Jew” working there. At the same time, she also experienced discrimination due to her engagement in the “Volksheimbewegung,” a community center movement that sought to establish public centers for youth, and was defamed as a Marxist Democrat. She also had numerous run-ins with the Hamburg State School Authority as she refused, for humanitarian reasons, to implement the educational methods required by the Nazis. This caused her increasing psychological and physical stress. In September 1933, the directorship of the Institute of Psychology was administratively transferred to National Socialist educational scientist Gustav Deuchler. Martha Muchow’s leave of absence from teaching was then suspended so that she was no longer able to work as a researcher at Universität Hamburg.

At this time point, Martha Muchow could no longer cope with the influence National Socialism was having on teaching and research conditions at Universität Hamburg, which had swiftly brought itself into line with Nazi philosophy after the National Socialists assumed power. She attempted suicide 2 days after termination of her employment and died as a result on 29 September 1933.

Research and teaching

In her research, postdoctoral psychologist Martha Muchow focused in particular on child psychology, kindergarten education, school organization, giftedness research, living environment theory, and developmental theory. Both in terms of perspective and methodology, she pursued a very diverse approach that united psychology and education, theory and empiricism as well as academic research and concrete practical application for solving social problems.

Also novel in her approach was the inclusion of children’s perspectives in interaction with their living environment and how children see, interpret, and live in the world around them. The hold true in particular of her primary work, Der Lebensraum des Großstadtkindes (The Life Space of the Urban Child), which was published after Martha Muchow’s death by her brother in 1935. As a pioneer work of German social research, it has become one of the most cited studies in contemporary research on childhood.

From 1926, she also played a key role in the development of the university teacher training degree program at Universität Hamburg when the University assumed responsibility for training of future primary and lower secondary teachers. She made sure that the teacher training program included a socio-educational pedagogic internship. From 1927, she also managed the internships in the field of child and adolescent psychology and, in addition to her academic work, accepted teaching contracts for psychology at the Fröbelseminar in Hamburg, a vocational school.

Commitment to social issues

Martha Muchow’s interdisciplinary research approach (i.e., her combination of psychological and socio-educational approaches) was also an expression of her practical orientation and her closely related socio-political engagement. In addition to her professional tasks, she was especially active in the “Volksheimbewegung,” which sought to build community centers for youth. She was a member of various working groups and committees in the “Gesellschaft für Freunde des Vaterländischen Schul- und Erziehungswesens,” a society for friends of the national school and educational system. She was also involved in the planning of daycare centers for urban children and was active in the kindergarten movement. This commitment was expressed in her work on the socio-educational journal Kindergarten – Zeitschrift des Deutschen FröbelVerbandes, des Deutschen Verbandes für Schulkinderpflege und der Berufsorganisation der Kindergärtnerinnen, Hortnerinnen und Jugendleiterinnen e.V.)

Martha Muchow actively worked to protect those politically prosecuted and ostracized following the assumption of power by the National Socialists.

Universität Hamburg and Martha Muchow

Martha Muchow’s influence on the contents of today’s educational science program at Universität Hamburg is omnipresent. Be it in recognizing the importance of and studying early childhood education and the role of childcare centers, research into childhood play, or the importance of facilities for today’s socialization processes—all of this is still part of the teaching curriculum in the educational sciences.

Martha Muchow is memorialized as a part of Universität Hamburg as well. The Martha Muchow Library (as the faculty library for educational science, psychology, and human movement science) was opened at Universität Hamburg in 2007.

Source: UHH / Denstorf

A Stolperstein (small brass “stumbling blocks” the size of small paving stones—10 by 10 centimeters—in which are inscribed the name and life dates of victims of Nazi persecution and extermination) in memory of Martha Muchow was placed in front of the main building of Universität Hamburg in 2010.

Source: Wikipedia.de

Further information and literature

Martha-Muchow-Stiftung (charitable foundation supporting early childhood and educational research)

http://martha-muchow-stiftung.de/

Martha Muchow Library https://www.ew.uni-hamburg.de/mmb/ueberuns/muchow.html

German-language tribute on the occasion of the opening of the Martha Muchow Library

https://www.ew.uni-hamburg.de/mmb/ressourcen/laudatio.pdf

Stolperstein in memory of Martha Muchow

http://www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de/index.php?MAIN_ID=7&BIO_ID=3117

October Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut

Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut

Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0 – Johndhall

In 1923, Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut became the first female doctor in the Faculty of Medicine at Universität Hamburg and the third female doctor in all of Germany to complete her Habilitation (postdoctoral qualification).

Elisabeth Amalie Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut was born on 21 June 1894 in Leipzig and died on 22 December 1993 in Rochester. Her father, Hugo Plaut, was a respected bacteriologist and her grandmother came from the Feist-Belmont family, owners of champagne production facilities still in existence today. She grew up near the Alster lake, together with her siblings Theodor, Hubert, and Carla. In order to protect their children from anti-Semitism, their parents first taught the children at home, giving particular emphasis to history and German. Liebeschütz-Plaut then went on to attend the Realgymnasium für Mädchen des Vereins für Frauenbildung, a girl’s high school in Hamburg. From 1913, Liebeschütz-Plaut first studied zoology and then switched to medicine. She completed her Habilitation at the Faculty of Medicine at Universität Hamburg in 1923. In 1933 the Hamburg Senate revoked her teaching permit due to her Jewish origins. Persecution by the National Socialists drove Liebeschütz-Plaut to emigrate to England with her family in 1938. She lived in, among other places, Winchester, Sutton, Epsom, and Liverpool. She was active in social and charitable causes until a very advanced age. In 1989 Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut, then 95, was invited as the guest of honor for the 100-year anniversary of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), where her Habilitation degree was restored. In the last years of her life, she lived with her daughter in Rochester. She died at 99.

Research and teaching

Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut first studied medicine at the University of Freiburg and Kiel University before switching to University of Bonn in 1916. She passed her state examination in medicine in spring of 1918 and then went on to earn her doctorate in Bonn. She acquired her first real experience as a doctor at 2 hospitals, the Israelitisches Krankenhaus and the Eppendorfer Krankenhaus in Hamburg, where she worked in 2 women’s stations and a pediatric station. She then worked as an assistant doctor in the general district hospital Allgemeines Kreiskrankenhaus in St. Georg (1919) and as a postdoctoral research associate (wissenschaftliche Assistentin) at the Physiological Institute of Universität Hamburg (1919–1924). In her research, Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut focused on gas exchanges in various diseases as well as muscle physiology, metabolic disorders, and defective heat regulation, publishing more than 25 papers between 1919 and 1925.

After the birth of her children and completing her Habilitation at the Faculty of Medicine at Universität Hamburg, she served as a Privatdozent (senior lecturer with no permanent teaching contract) for physiology from 1923 to 1933. As a result of her marriage to Hans Liebeschütz (1893–1973) in 1924, she had to give up her position as an assistant doctor. A legal provision on dual-income families prohibited married women from holding a job in public service at that time. After being dismissed, Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut taught for some time at a Jewish domestic science school as well as the Israelitische Krankenhaus. From 1924 to 1933 she also worked as a doctor in private practice for a private clinic specializing in metabolic disorders.

In July 1933, the Hamburg Senate revoked Liebeschütz-Plaut’s teaching permit and her Approbation (license to practice medicine) for being a “non-Aryan.” This fate was shared by 500 other medical doctors Hamburg, both students and university teachers, who lost their livelihoods under National Socialism. Even in 1946, when the British military administration demanded the names of those who had been wrongfully dismissed and their return permitted, nothing was done to remedy this situation.

In 1938 she and her husband moved to England, although they could no longer teach or research because their professional qualifications were not recognized there. Liebeschütz-Plaut devoted herself to social causes instead, working for the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS) until she was 91.

After Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut became the first woman at the Faculty of Medicine at Universität Hamburg to earn her Habilitation, it took 36 more years until Hedwig Wallis (1921–1997) became the second woman and doctor at Universität Hamburg to do the same.

Source: UKE / Museum of Medical History

Commitment to social issues

Although she obtained a job with the opportunity to complete her Habilitation in Otto Kestner’s laboratory despite her outsider status as a woman and a Jew at that time in history, Liebeschütz-Plaut was repeatedly subject to discrimination in her work in the register of Hamburg doctors at the Faculty of Medicine. As a woman, she was, for example, prohibited from entering the cafeteria. This location was reserved for male doctors, who ate and spent their leisure time there. Liebeschütz-Plaut had to eat at a table reserved exclusively for women. An assistant doctor who called her to the telephone inside the cafeteria was even forced to pay a fine because women were prohibited there.

In 1930, she added her signature to a letter from Hamburg doctors to the Hamburg public health authority, protesting the placement of condom dispensing machines for moral and ethical reasons. In 1930/1931, Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut held a presentation for the members of the local Hamburg division of a German doctors association on the visionary women’s mysticism of the Middle Ages from a medical/psychological standpoint

It was this experience and her own emigration that inspired her to actively seek to help women and children in need. After emigrating to England, she served as a social worker for children from 1938 and later as a geriatric nurse for the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, a voluntary organization founded in 1938 to help people in desperate need.

Universität Hamburg and Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut

Even now, decades after her work here ended, Liebeschütz-Plaut has had a lasting impact on Universität Hamburg and the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE). The UKE mentoring program, named after her, has been promoting Habilitation projects from female doctors and early career researchers since 2014 to increase the percentage of women in leadership positions in medicine in the mid- and long-term future.

The exhibition room “Ärztin werden” (becoming a female doctor) opened in the Museum of Medical History at the UKE in June 2019, offering visitors a closer look at the life and lasting impact of Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut.

Source: UKE / Museum of Medical History

Further information

Brief German-language biography on the web pages of Charité Berlin

Entry in the German-language biography website Deutsche Biographie

Literature

Kaiser von Holst, Silke: “Liebeschütz-Plaut, Rahel.” in: Hamburgische Biografie. Volume 1. Hamburg 2001, pp. 185–186.

Fischer-Radizi, Doris: Vertrieben aus Hamburg.Die Ärztin Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut. (= Wissenschaftler in Hamburg 2). Göttingen 2019.

September: Dorothea Frede

Dorothea Frede

Image: UHH/Frede

In 1991, you became the first female philosophy professor at Universität Hamburg. Can you still remember your first day of work?

I can remember it well for a very special reason: when I left home in early April 1991 for my first day of work at Universität Hamburg, I remembered that on that very day 30 years previously, I had left the exact same location, where I was staying at relative’s house on the Outer Alster Lake, to make my way to the University as a first semester student. Lots of other things had changed in that time, of course, including myself. I had already spent 20 years teaching in the United States when I was appointed a professor in Hamburg. The fact I was so familiar with Hamburg made it easier to quickly become re-accustomed to what were still at the time rather chaotic conditions at a German university. The philosophers were still in the tenth floor of the Philosophenturm, so I felt at home again right way even though none of the faces I once knew were still there.

Can you tell us a little about your academic career and your work as a philosophy professor from 1991?

As I mentioned before, I began my studies in Hamburg in 1961, originally in German linguistics and musicology. After 3 semesters I switched to philosophy, with a specialization in the history of philosophy, and classical philology. In fall 1963 I continued my studies at Universität Göttingen, and in summer 1968 I earned my doctorate from Günther Patzig with a dissertation on Aristotle. I then had a three-year scholarship from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG).

In 1971 I emigrated to Berkeley, California, together with my husband Michael Frede. After giving birth to my 2 children in 1970 and 1972, I worked as a part-time lecturer, first in California and then in and around Princeton, New Jersey. Between 1978 and 1985 I worked full-time as an assistant professor at Rutgers University. I was then an associate professor at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania until 1991.

From 1991 until my retirement in 2006, I was a professor of philosophy in Hamburg. After retiring, I taught as an adjunct professor at the University of California Berkeley until 2011 and as a visiting professor at the University of Toronto until 2015. Since then, I have focused on my own work on the history of philosophy, although I am offering 1 more lecture on Aristotle this semester in Hamburg.

The option of working part-time was very important. This was the only way for me to balance caring for my 2 children with the pressure to publish and visit international conferences, which are very important for getting tenure in the United States. In the sheltered slipstream of these early years, I could also see how opportunities for women were gradually improving at universities. That benefited me when I took a full-time position in 1978.

All of that was behind me when I started teaching at Universität Hamburg in 1991. Given my past experience, I quickly became active in academic self-governance, initially in what was then the Department of Philosophy and Social Sciences, and from 1995 to 2000 in the Academic Senate as well. Teaching at Universität Hamburg was always a pleasure for me. The students clearly enjoyed being challenged to read and present on difficult texts on the history of philosophy, and they appreciated it when a lecturer took time for them and lessons were well organized.

As a woman, where did you experience obstacles in philosophy? And was there any way you might have actually benefited from being a woman?

I repeatedly encountered obstacles (even still in Hamburg) in that a woman was not taken totally seriously. It took a lot not to let myself be intimidated or overrun. However, from the mid-1980s, philosophy departments in the United States found themselves having to carefully review applications from women—this worked to my advantage. This likely benefited me in Hamburg as well. A male applicant from the USA would probably not have been invited to lecture. In my subject area of ancient philosophy, however, there were highly respected female specialists in the Anglo-Saxon regions early on. As a result, there was less bias than in other areas of philosophy. What’s more, I was part of a relatively small community whose members treated each other with goodwill and respect, men and women alike. However, some honors, invitations, and memberships were doubtless bestowed on me because I am a woman. In my generation, women were still rare. As a result, schools had to fight hard for the few female academics available when they needed to increase the share of women among their teaching staff.

It has been 25 years since you became a professor. From your perspective, how has the position of women in the discipline of philosophy changed in this time?

Once they have made it past all the hurdles, women are now treated equally and fairly. Today woman are no longer evaluated in a patronizing, disparaging manner, as was often the case thirty years ago.

However, women are still underrepresented in the Department of Philosophy, especially among the professors and academic staff. If you could, what would you tell existing or perspective female philosophy students from your experienced perspective?

The percentage of female professors in philosophy, especially as compared to the other humanities, is still low both in Germany and elsewhere. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, in light of the very uncertain future career outlook in this ‘not very lucrative’ subject, women are in my experience more likely than men to make pragmatic decisions about their goals after earning an MA. I have seen especially highly promising young women decide not to pursue a doctorate in order to take a safe job in industry, radio, or television. Secondly, women feel repelled by the sometimes overly casual or even gruff discussion culture in the world of philosophy. That applies to both the USA and Germany, in my experience. When the loudest and most aggressive participants set the tone, women often go silent. As a result, the number of qualified women decreases over the course of studies. And this trend only becomes stronger in the pursuit of further qualifications, leaving few female applicants for a professorship.

As good advice, I can only encourage young women not to let themselves be led astray when they want to pursue this path. However, in light of the few available jobs in philosophy, it is a risk. From a certain age, there are few alternatives. Even in my case, sometimes it was only luck that helped me. But you cannot depend on luck and there is no sure recipe for a successful future career in philosophy.

August: Heidrun Hartmann

Heidrun Hartmann

Photo: Wilfried Hartmann

The botanist Heidrun Hartmann was a passionate explorer, author, and instructor at Universität Hamburg.

Heidrun Elsbeth Klara Hartmann (née Osterwald) was born on 5 August 1942 in Kolberg (now Poland) and died on 11 July 2016 in Hamburg. From 1969 to 2007, Heidrun Hartmann was active as a researcher and instructor in general botany in the Department of Biology at the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences (MIN), the Institute of Plant Science and Microbiology, and the Botanical Garden.

As a result of her commitment to research and teaching over more than 35 years at Universität Hamburg, she received numerous tributes and awards both during her lifetime and posthumously, including having a plant genera and 2 species named after her in honor of her discovery.

She had 2 daughters together with her husband Wilfried Hartmann, a professor of comparative and international education at Universität Hamburg.

Academic background

After completing her Abitur (German secondary school leaving certificate) in Hildesheim with an emphasis on the natural sciences and math, Heidrun Hartmann initially began teacher training for biology in 1962 at Universität Hamburg. After several semesters and various social internships, she switched to the degree program in biology. She was able to acquire extensive early experience during various excursions and in her work at the Biological Institute Helgoland. She was also granted a scholarship to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem funded by the International Association for the Exchange of Students for Technical Experience (IAESTE). This 2-month stay lastingly shaped her interest in desert and steppe regions.

After successfully completing her Diplom degree examination, she worked as a lecturer at the Institute for General Botany and Botanical Garden. After earning her doctorate in 1973, completing her Habilitation (postdoctoral qualification) in 1981, and earning the venia legendi (teaching authorization) for the subject of general botany, she joined the ranks of female professors. She then remained a professor until retiring in 2007.

Biologist Heidrun Hartmann with a colleague conducting field research in South Africa in 1982 (photo: Prof. Dr. Sigrid Liede-Schumann, Bayreuth).

Core research areas

Heidrun Hartmann’s primary research interest was the classification of succulent plants. From 1969 she focused on the Aizoaceae plant family (commonly known as ice plants in English) on all continents. Hartmann conducted field research in Africa, South America, the southern United States, and the United Arab Emirates, among other places. For herbarium work, she also traveled to China, Great Britain, Finland, Sweden, and the United States, further honing her international research profile. She published her research results on taxonomies of genera, species, and adaptation patterns in over 130 publications in many languages.

In her dissertation in 1973, Heidrun Hartmann revised the genus of the ice plant family, reducing the number of species from 100 to 10. Her research drew responses both from international specialist associations as well as from collectors and agriculturists outside the scientific community. A 2-volume handbook in English, the second completely revised edition of which she finished shortly before her death, is currently regarded as the standard reference work for the Aizoaceae family.

Commitment and awards

Hartmann’s research achievements and her international publications and presentations in more than 23 countries bear testament to her specialist knowledge in the field of succulents. She was a member of the Linnean Society, the Association for the Taxonomic Study of the Tropical African Flora (AETFAT), the Association Internationale des Amateurs de cactus et Plantes Succulentes (AIAPS), and the International Organization for Succulent Plant Study (IOS). The genus Hartmanthus was named in her honor in 1996, followed by the species Gibbaeum hartmannianum in 2012, and the species Delosperma heidihartmanniae in 2018. She received the South African Kirstenbosch Jubilee Award in 1977 in recognition of her accomplishments as an early career researcher and the Swedish Linné Medal in 2007. In 2012 she was granted the IOS organization’s Cactus d‘Or Award, created by Princess Grace of Monaco and awarded every 2 years. In 2015 the Cactus and Succulent Society of America (CSSA) bestowed its highest honor on her, naming her a Fellow.

Botanist Heidrun Hartmann conducting field research in Lesotho 1982. Her bag contains 2 cameras for photos and slides to document her research (source: Prof. Dr. Sigrid Liede-Schumann, Bayreuth).

Universität Hamburg and Heidrun Hartmann

Heidrun Hartmann was passionate about studying, teaching, and researching at Universität Hamburg, even though her mobility was limited later in life. She also spent several years as the director of the Classification department and was the doctoral committee chairperson for the Department of Biology. Her academic work was assisted by 600m2 greenhouse space and gardening assistance made available to her in the Botanical Garden, which helped to house the living plants she brought back from her numerous field expeditions.

From 1969, Heidrun Hartmann collected some 45,000 black and white photos and slides in a reference collection, many of which have also been digitalized. She also developed her own database in which she stored approximately 15,000 data records, her own collections, and records of research work with students and colleagues. The materials are currently kept as a research and memorial library dedicated to Heidrun Hartmann’s memory in the Botanical Institute of Universität Hamburg.

Further information

Hamburger Professor*innenkatalog (German-language catalog of professors at Universität Hamburg)

Research profile in the Section Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants (BEE)

July: Agathe Lasch

Agathe Lasch

Photo: bpk / Staatsbibliothek

Agathe Lasch was not only the first female professor at Universität Hamburg, she was also the first female professor for German studies in the whole of Germany, as well as the founder of the study of Middle Low German as a language.

Agathe Lasch was born on 4 July 1879 in Berlin, the third of 5 children of a Jewish merchant family. She began studying German philology and Scandinavian studies in Heidelberg in 1906 and in 1923 became the first female professor in Hamburg and the first female professor of German studies in Germany. She taught and researched within the scope of her professorship for lower German linguistics at Universität Hamburg until 1934, when she was stripped of her professorship due to her Jewish origins after the National Socialists assumed power. Because she was also affected by a ban on publishing and could not find a position abroad, her academic career was effectively over. She and her sisters were ultimately deported to Riga, Latvia, by the National Socialists in August 1942. Agathe Lasch died on 18 August 1942 together with more than 1,000 others who were deported at the same time.

Her memory remains, however. She was not only the founder of the study of the Middle Low German language and one of the first female professors in Germany, as a Jewish woman, she also successfully mastered her path at the University and supported female students both as a mentor and a (financial) sponsor.

Research, teaching, and works

After studying German philology and Scandinavian studies, Agathe Lasch earned her doctorate in 1909 with a doctoral thesis on the subject of the history of written language in Berlin through the middle of the sixteenth century. She then spent 7 years in the United States, teaching and researching at Bryn Mawr, a women’s college in Pennsylvania, in the Department of German and German Studies. During this time, Agathe Lasch specialized in the Lower Middle German language and in 1910 published a book on it entitled Mittelniederdeutsche Sprache, which remains a standard text in German philology until today. This book is also the reason that she is considered the founder of the study of the Middle Low German language. In this book, like all of her work, Agathe Lasch pursued a special research approach. In order to systematically describe a language and in particular to understand the history of a language, she believed it necessary to take into account not only the cultural development of the language but also the contemporary political and historical developments. This means linking language history with political history and the social factors in effect at that time.

After returning to Germany in 1917, Agathe Lasch initially worked as a research associate and later as the head of the Sammelstelle für das Hamburgische Wörterbuch, an information collection office for a dictionary on the Hamburg dialect, at the German Seminar of the Colonial Institute in Hamburg. After the founding of Universität Hamburg, she completed her Habilitation (postdoctoral qualification) there in German philology in 1919. In 1923, she became the first woman in Hamburg and the first female Germanist in all of Germany to become a professor. She did not receive the chair for Low German Philology at Universität Hamburg until 3 years later, however. Agathe Lasch focused in particular on 2 large projects within her core research area—the compilation of the Hamburgisches Wörterbuch, a dictionary of the Hamburg dialect, and the Middle Low German Dictionary. These dictionaries are still regarded as central reference works for historical Lower German linguistics.

When the National Socialists assumed power in 1933 and banned people of “non-Aryan origins” from employment, Agathe Lasch was still able to spend several more months researching and teaching at Universität Hamburg despite her Jewish origins thanks to the dedicated efforts of several students and Scandinavian Germanists. In 1934 she took early retirement and was banned from publishing any further works in Germany. Before being deported in 1942, she published occasional articles in Scandinavian magazines with the help of her students, who supplied her with literature. She sought a position abroad, but was prevented from taking any of them by the German government.

Despite the abrupt end of Agathe Lasch’s academic career, she achieved her goal of establishing Lower German philology as an academic discipline, in particular in Hamburg.

Universität Hamburg and Agathe Lasch

Agathe Lasch’s memory lives on in the City of Hamburg and at her university. To commemorate her professional competence and the trailblazing role she played in making Low German the subject of academic study, the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg created the Agathe Lasch Prize, which began in 1992, and is bestowed on a female early career researcher in the field of the Low German language every 3 years. To mark Lasch’s special commitment to women in academia, the Equal Opportunity Unit introduced the Agathe Lasch Coaching Program in 2013 to promote equal opportunity for female junior professors and female academics working on their Habilitation at Universität Hamburg. Lecture Hall B in the Main Building of the University has also been named in honor or Agathe Lasch and a “stumbling block” (small brass “stumbling blocks” the size small paving stones—10 by 10 centimeters—which bear the name and dates of victims of Nazi persecution) placed in front of the building in her memory.

Further information

Agathe Lasch Coaching + Diversity at Universität Hamburg: www.uni-hamburg.de/gleichstellung/foerderungen/agathe-lasch-coaching

Agathe Lasch Prize offered by the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg: www.agathe-lasch.de/Agathe-Lasch-Preis

Literature

Kaiser, Christine M. (2011): “‘ ... ausnahmsweise eine weibliche Kraft.’ Agathe Lasch ˗ die erste Germanistikprofessorin Deutschlands am Germanischen Seminar der Hamburger Universität.” in: Mirko Nottscheid/Myriam Richter (eds): 100 Jahre Germanistik in Hamburg.Traditionen und Perspektiven. In cooperation with Hans Harald Müller and Ingrid Schröder. Berlin/Hamburg, pp. 81–105.

Maas, Utz (2018): Verfolgung und Auswanderung deutschsprachiger Sprachforscher 1933–1945. Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung (ZfL): https://zflprojekte.de/sprachforscher-im-exil/index.php/catalog/l/298-lasch-agathe (last accessed on 29 April 2019).

Möhn, Dieter (2002): Die Geschichte in der Sprache.Die Philologin Agathe Lasch. Lecture on the occasion of the naming of Lecture Hall B in the Main Building of Universität Hamburg as the “Agathe Lasch Lecture Hall” on 4 November 1999. in: Zum Gedenken an Agathe Lasch (1879–1942?). Speeches on the occasion of the naming of Lecture Hall B in the Main Building of Universität Hamburg as the “Agathe Lasch Lecture Hall” on 4 November 1999. Hamburg, pp. 14–27.

Nottscheid, Mirko, Kaiser, Christine M., Stuhlmann, Andreas (eds) (2009): Die Germanistin Agathe Lasch (1879–1942).Aufsätze zu Leben, Werk und Wirkung. Nordhausen (also: information. Zeitschrift für Bibliothek, Archiv und Information in Norddeutschland 29).

Priebe, Anna Maria (2014): “Agathe Lasch.” in: 19neunzehn – Magazin der Universität Hamburg (3), pp. 38–39.

Schröder, Ingrid (2011): “’... den sprachlichen Beobachtungen geschichtliche Darstellung geben’ - die Germanistikprofessorin Agathe Lasch.” in: Nicolaysen, Rainer (ed): Das Hauptgebäude der Universität Hamburg als Gedächtnisort.Mit sieben Porträts in der NS-Zeit vertriebener Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler. Hamburg, pp. 81–111 (also available online at: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/opus/volltexte/2011/112/chapter/HamburgUP_Hauptgebaeude_Schroeder_Lasch.pdf).

June: Ulla Knapp

Ulla Knapp

Photo: Gerhard Will

Finally focusing on women—this was the underlying theme of Ulla Knapp’s academic career as the first professor of economics with a gender orientation in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Ursula Knapp, known for short as “Ulla,” was born in the town of Velbert in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia in 1952. After studying economics at Universität Bochum and Universität Gießen, she was initially employed there as a research assistant. From 1977 she worked as a research assistant at what was then known as the Comprehensive University of Wuppertal before earning her doctorate with Prof. Dr. Sigrid Metz-Göckel (Technische Universität Dortmund) in 1983. Her dissertation, entitled Vermarktung der Arbeit und weiblicher Lebenszusammenhang.Hausarbeit und geschlechtsspezifischer Arbeitsmarkt in Deutschland bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik, was on the labor market and women’s role in it, specifically house work and the gender-specific labor market in Germany through the end of the Weimar Republic. After earning her doctorate, she traded the academic arena for the political one, becoming an advisor for gender equality policy and the labor market in the Ministry for Economic Affairs of North Rhine-Westphalia, where she headed the ministerial department from 1991. Her son was born the same year. The following year, she was appointed to the first women’s research professorship at Hamburg University of Economics and Politics (HWP). When HWP was integrated into the newly founded Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences at Universität Hamburg in 2005, Ulla Knapp’s professorship became a part of the University as well. Ulla Knapp spent a total of 18 years teaching and researching within the scope of this professorship. In October 2010, Ulla Knapp died at age 58 after a long battle with severe multiple sclerosis.

Research and teaching at HWP

Her appointment to HWP in Winter Semester 1992/93 as a professor of economics with a gender orientation also had important structural ramifications for both the field of study and for the university itself. The professorship on the topic of “economics of gender relations” was established despite resistance from the Hamburg State Ministry for Science and Research (BWFG) and blazed a trail for inclusion of the gender perspective in the (economic) sciences.

In her research, Knapp focused in particular on the interplay of employment, unemployment, and gender relations from a macroeconomic standpoint. This focus on economic conditions for women was also reflected in her lectures on “labor market and employment” and “economics of gender relations.”

Her academic work was shaped by her passionate fight to combat discrimination against women. In dealing with the strongly male-dominated economics review board, Ulla Knapp challenged her specialist discipline with provocative publication titles such as: “An Introduction to Economics for Non-Mathematicians, Women, and Other Minorities. Ulla Knapp always sought not only to use traditional academic methods to analyze the lack of equality for women but also to critically analyze these methods themselves. In so doing, it became clear that the patriarchal viewpoint in the field economics effectively ignores women by leaving unpaid work out of economic analyses.

In research and teaching, Ulla Knapp espoused an interdisciplinary approach in which she made it clear that economics and sociology share a common origin and cannot be separated from one another academically, while at the same time always viewed conditions from a historical standpoint. As a vehement critic of neoliberalism, she consistently fought the field’s neoclassical orientation and actively encouraged the use of a variety of methods and the inclusion of ecological and feminist perspectives. Her former department, now Socioeconomics, was shaped by this academic approach, which still prevails today at the University.

Political and personal engagement

Ulla Knapp always combined her academic work with political action. She was not just a careful observer of new social movements, but regarded herself as a part of them. She therefore wrote articles for various magazines in order to provide academic findings that may influence the direction of these movements.

The close link between academia and promotion of equal opportunities for women was already evident in her engagement in the Arbeitskreis Wissenschaftlerinnen von NRW, a research group on female academics in North Rhine-Westphalia, which she used in the 1980s to support the first job creation measures for unemployed female academics. Knapp sought to achieve equal opportunity for women through institutional measures, and was one of the first proponents of establishing a representative for women’s issues at the Comprehensive University of Wuppertal.

In later years she was also actively involved in bringing women, in particular female academics, together so they could organize themselves for common purposes. She was among the founding members of female economists network efas (economics, feminism, and science), which provided her with professional networking opportunities for academic exchange and cooperation from 2000. Here, too, her ultimate goal was the further development of content. In 2007, for example, she expressed the desire to learn “more about ‘global feminism,’ such as about women in developing and transformation countries or the impacts of financial capitalism, etc.)” at joint network conferences (Knapp 2007).

Following Ulla Knapp’s death in fall 2010, her exceptional dedication, her intensive support in particular of female students, and her deep love of the department inspired students, colleagues, her husband, and others who had been touched by her life to compile memories of her and her work and save them as an anthology that will forever serve as a tribute to her impact and a point of reference.

Further information

Knapp, Ulla (1997): “Ökofeministisch wirtschaften?” in: Ökologisches Wirtschaften Spezial 3/4 1997. oekologisches-wirtschaften.de/index.php/oew/article/download/888/888 (download on 22 May 2019).

Knapp, Ulla (2007): “Steckbrief.” In: efas Newsletter No. 10/2007. https://efas.htw-berlin.de/wp-content/uploads/newsletter-10.pdf (last accessed 28 May 2019).

Schmidt, Cornelia (2011): “Pionierfunktionen für mehr gender awareness übernehmen.” A personal obituary for Ulla Knapp. https://efas.htw-berlin.de/index.php/in-erinnerung-an-ulla-knapp (downloaded on 22 May 2019).

Unknown (2011): “Nachruf Ulla Knapp.” in: VMP9 – Das Magazin für den Fachbereich Sozialökonomie.https://gdff.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/GDFF-VMP9-DasMagazin_Ausg07_2011_04.pdf (downloaded on 22 May 2019).

May: Hedwig Klein

Hedwig Klein

Photo: Hamburg State Archive

The Arabist Hedwig Klein still had her academic career in front of her when she was deported by the National Socialists and murdered in Auschwitz. The few years in which she was academically active, however, were characterized by her great commitment to Islamic studies, in particular her role in helping to compile a large Arab-German dictionary.

Hedwig Klein was born on 2 September 1911 in Antwerp, Netherlands, and grew up in the Hanseatic City of Hamburg from 1914. Her father, a Hungarian merchant, died in 1916 as a soldier on the Eastern Front in the First World War. Together with her older sister, mother, and grandmother, Klein spent her childhood and youth in Hamburg, attending the Israelitische Höhere Mädchenschule, a secondary Israeli school for girls, from 1918. She successfully passed her school leaving examination in spring of 1931 and quickly enrolled in Universität Hamburg, beginning with Islamic studies, Semitic studies (comparative linguistic studies of the Semitic languages) and English philology in the summer semester of that year. Once the National Socialist German Workers“ Party came to power, Hedwig Klein did not escape the consequences of the increasing discrimination against the Jewish population. A circular issued in 1937 forbade the award of doctorate titles to German Jews. Nevertheless, with the help of the dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, Wilhelm Gundert, and her doctoral supervisor, Rudolf Strothmann, Klein was able to register for her doctoral thesis, a critical edition of an Arab manuscript from early history, and received the grade “with distinction” for both the written thesis and her oral defense. In late 1938, however, the newly appointed dean Fritz Jäger withdrew permission to publish her thesis and refused to award Klein her doctoral title due to her Jewish origins. On 18 August 1939, Klein left Germany as a result of the increasing persecution of the Jews and her lack of any hope in finding employment. With the help of Carl Rathjens, Klein attempted to sail to India, where Rathjens had found her a job in an Arabist project. Due to the approaching World War, however, all German ships were ordered back to their home ports on 27 August 1939. Among the many ships returning to port was the one carrying Hedwig Klein back to Hamburg.

Academic commitment

Following her failed attempt to emigrate to India, Klein was able to assist in preliminary work for the Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart, (Dictionary of modern written Arabic), in August 1941 with support from Arabic studies instructor Arthur Schaade and under the supervision of Hans Wehr. The dictionary would later be used to translate the book Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. Klein wrote entries for the meaning of individual Arab terms for the dictionary, receiving 10 pfennigs per definition. Both Schaade and Wehr actively worked to save the Jewish Arabist, preventing her deportation to Riga by emphasizing Klein’s importance to the project. Klein’s sister, however, was unable to avoid deportation and was murdered by the National Socialists. Although Klein continued to work on the dictionary, her situation rapidly deteriorated. In 1942, Klein, her mother, and her grandmother were forced to move to a “Jew house” in Hamburg and their own apartment was expropriated. She was unable to avoid the second deportation order. On 11 July 1942, Hedwig Klein and thousands of other people were deported directly from Hamburg to Auschwitz. It is impossible to determine exactly when and how Hedwig Klein was murdered.

Posthumous recognition

After the end of the Second World War, Carl Rathjens sought to have Klein’s doctoral dissertation published and her doctoral title awarded to her posthumously. Hedwig Klein was officially awarded the title Doctor of Philosophy on 15 August 1947. The Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart dictionary which Klein worked on until her deportation was not published until 1952. Known as the “Wehr” for short, it is now the most-used Arabic dictionary worldwide. Hedwig Klein’s name appears only in the preface to the first edition as a contributor. Her subsequent fate remains unmentioned.

On 22 April 2010, Universität Hamburg had Stolpersteine (small brass “stumbling blocks” the size small paving stones—10 by 10 centimeters—which bear the name and dates of victims of Nazi persecution) placed in front of the Main Building at Edmund-Siemers-Allee 1 to memorialize Hedwig Klein and 9 other victims of the Nazi regime.

Literature

Freimark, Peter (1991): “Promotion Hedwig Klein – zugleich ein Beitrag zum Seminar für Geschichte und Kultur des Vorderen Orients.” in: Eckhart Krause, Ludwig Huber & Holger Fischer (eds), Hochschulalltag im »Dritten Reich«.Die Hamburger Universität 1933-1945. Teil II:Philosophische Fakultät Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Fakultät (Vol. 3). Hamburg: Dietrich Reimer Verlag. pp. 851–859.

Maas, Utz (2018): Klein, Hedwig. Available online at: http://zflprojekte.de/sprachforscher-im-exil/index.php/catalog/k/282-klein-hedwig.

Universität Hamburg (2010): “Stolpersteine an der Universität Hamburg verlegt.” Available online at: www.hamburg.de/wissenschaftslandschaft-hamburg-aktuell/2221212/stolpersteine-uhh-22-04-2010.html.

Buchen Stefan (2018): Die Jüdin Hedwig Klein und „Mein Kampf“.Die Arabistin, die niemand kennt. Available online at: https://de.qantara.de/inhalt/die-j%C3%BCdin-hedwig-klein-und-mein-kampf-die-arabistin-die-niemand-kennt.

April: Anna Siemsen

Anna Siemsen

Photo: AdsD / Friedrich Ebert Foundation

Anna Siemsen’s educational career and political engagement made her a unique woman for her time.

Anna Siemsen was born on 18 January 1882 in the village of Mark in Westphalia. After successfully completing her doctoral studies and state examination, she worked as a Gymnasium (college-prep high school) teacher for several years before switching to educational administration. Originally appointed to the Friedrich Schiller University Jena in 1923 as a lecturer, she later became an adjunct professor for education. In addition to her work in education science, Anna Siemsen was always politically active. She was a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and a contributor to various socialist newspapers.

National Socialism forced her to emigrate to Switzerland in 1933. She was granted Swiss citizenship and a work permit there and remained politically active. In exile, she worked to help Germany establish a democratic educational system following the end of the Nazi regime.

After returning to Germany in 1946, she worked as a lecturer at Universität Hamburg and actively supported the peace movement, international goodwill, and European unification. Anna Siemsen died on 22 January 1951 in Hamburg.

Teaching and works

Anna Siemsen initially attended a secondary school for girls in Hamm, but was forced to leave due to poor health. She prepared for her teaching exam by herself and passed in 1905. Siemsen later earned her doctorate with distinction in Bonn and also passed her state examination for secondary education with outstanding results. Afterwards, she spent 10 years working as a Gymnasium teacher.

In 1920 she was appointed as the first female alderman for educational issues of the City of Düsseldorf. In this capacity, she worked to reform the vocational and trade school system, an area in which she would remain active in the years to follow. After spending some time as a Oberschulrätin (school inspector) in Berlin, she was appointed as a lecturer in Thuringia, where she was tasked with organizing the secondary education system. This work was also associated with an adjunct professorship for education at Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

When the socialist-led Ministry of Thuringia was dissolved by the Reichswehr, Germany’s military organization at the time, Anna Siemsen’s adjunct professorship was revoked in 1932. She then emigrated to Switzerland, where she helped organize teacher training courses, among other things. Siemsen understood early on that Germany would require new teachers after the fall of National Socialism. She wanted to help develop a democratic educational system for Germany.

In 1946, Anna Siemsen returned to Germany. She began working for Universität Hamburg in the following year as a Oberstudienrätin (senior counselor of studies) after being promised that all her years of service would be recognized. For various reasons, including budget constraints of the City of Hamburg, Anna Siemsen’s advanced age, and her Swiss citizenship, the job promised to her could not be implemented as planned. Although she was put in charge of the urgently required post war programs to train teachers for adult education centers and received a teaching contract for European literature, she was not given another professorship.

Political activism

As a socialist educator, Anna Siemsen regarded education as political and inseparable from social, cultural, and economic contexts. In her publications, she placed special emphasis on the problems unique to women such as dual burdens from housework and urgently necessary gainful employment.

Because hardly any of Anna Siemsen’s writings were reprinted after her death, her educational works were largely forgotten. Yet her educational career and the professorship she was granted made her a unique woman for her time.

Anna Siemsen was very active in politics as well as education. She always positioned herself on the left, as a social democrat and a socialist.

After the First World War she joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschland, USPD). Later she became a member of the SPD and served as a representative for the party in the Reichstag from 1928 to 1930. In the fight against fascism, Anna Siemsen joined the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany (Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschland, SAPD) in 1931 and assumed an important role in the social democratic, pacifist wing there. In addition to her political engagement, she served as an author and editor for various socialist newspapers and was a member of the board of the German League for Human Rights as well as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

After returning to Germany, Anna Siemsen worked as a member of the SPD and a pacifist to promote international goodwill, democratic principles, and European unification.

Universität Hamburg and Anna Siemsen

Although the relationship between Universität Hamburg and Anna Siemsen was not free of tension, the educational science lecture hall, now known as the Anna Siemsen Lecture Hall, was named in her honor. In 2005, after extensive renovations, the lecture hall was christened in a festive ceremony that also highlighted Anna Siemsen’s achievements in the field of educational science.

Photo: UHH/Möller

Further information

Entry on Anna Siemsen in the women’s biography database of the City of Hamburg

March: Asta Hampe

Asta Hampe

Asta Hampe 1935 Source: DAB

Asta Hampe represents a generation of women who lived from the turn of one century to the next, making their own path in life in defiance of contemporary societal expectations. In this, Universität Hamburg played a significant role.

Asta Hampe was born on 24 May 1907 in Helmstedt, Lower Saxony, and developed an interest in technology at a young age. Her father and uncle used to take her to their family-run wool spinning mill and silk factory, staffed mainly by women, when she was a mere toddler. The early twentieth century witnessed several significant technical inventions, including broadcasting technology and the first airship ever to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Asta Hampe was still a schoolgirl when she built her own radio. She completed a degree in engineering at the Munich University of Applied Sciences with support from her uncle and grandfather, who paid for her studies. After she graduated, her career took her to every corner of the country. She also traveled to London, Sheffield and Exeter in 1929 and 1935 to study English. In 1974, after her retirement, Asta returned to her home town of Hamburg, where she lived until her death on 22 October 2003 at the age of 93.

Studies and first career stages

Around 500 men and 5 women were enrolled at the Munich University of Applied Sciences in the 1927/28 Winter Semester. The admission of these women did not go without comment—during their first weeks, the young men would stomp their feet noisily to ‘greet’ their female fellow students whenever they entered the lecture hall. Asta transferred to the Technical University of Berlin after her preliminary examination to study telecommunications. By then, conditions for female students had begun to improve. Nonetheless, she was one of only 3 women among 200–300 male students. During her studies, she established contact with the German female academics’ society, the DAB, which ran a women’s dormitory in Berlin.

Asta went on to work at the Krupp research institute for a year after graduating and later transferred to Barmbek Hospital in Hamburg, where she took up a position as a resident physicist. National Socialism was on the rise, making it increasingly difficult for female academics to keep working. Asta Hampe was dismissed in 1933 after only 6 months in her job: physics was no longer considered an appropriate career for a woman. For the following 18 months, she worked as a draft engineer for an export firm.

She then took up a position as the head of a testing laboratory at Philipps-Valvo. Asta was not satisfied with her new job and wanted to leave, but she knew perfectly well that she could not simply quit a company that was considered instrumental to the wartime effort unless she had another position waiting for her. In 1939, she applied for a post as a navy physicist. She was accepted and left Philipps-Valvo in favor of her new contract with the communications research headquarters of the German navy. Women were not allowed to work on the ships, so Asta had to stay in the laboratory while the men on the decks tested her work. Asta Hampe joined the Nazi Party in 1939, probably as a result of her work for the German navy.

A change in direction

Asta Hampe returned to Hamburg for personal reasons in 1942 and embarked on a degree in economics at Universität Hamburg. Five years later, in 1947, she completed her doctoral dissertation on the impact of wartime destruction on urban land credit.

She became an adjunct lecturer in statistics at Universität Hamburg and the assistant of Professor Albert von Mühlenfels in 1951. Following her habilitation (postdoctoral qualification) in 1957, Asta Hampe was awarded an extraordinary professorship. Six year later, she was appointed to the newly founded Chair for Business Mathematics at the University of Marburg, where she seized the opportunity to establish the new discipline from the ground up and shape the careers of an entire generation of economists. Between 1968 and 1969, she was the dean of the Faculty of Law and Public Administration of the University of Marburg.

Commitment to social issues

Throughout her life, Asta Hampe campaigned for gender equality in academia. She founded the German association of female engineers (Gemeinschaft Deutscher Ingenieurinnen) when she was a student in Berlin; in 1931, her association became a member of the German female academics’ society (Deutscher Akademikerinnenbund, DAB). She was also one of the founding members of the Hamburg branch of the DAB, established in 1947. Within the DAB, she managed the committee for higher education from 1958 and 1963 and, again, from 1976 until 1981. Asta attended DAB events well into her senior years. In 1990, she initiated and co-founded the German association of women university teachers. It was one of the final achievements of her long and productive life. Asta Hampe was a member of numerous academic associations and a permanent member of the advisory committee of the German Federal Ministry of Construction until its closure.

Further information

Hamburg women’s biographies: Asta Hampe

University Women’s International Networks Database

Literature

Maul, Bärbel, 2002: Akademikerinnen in der Nachkriegszeit.Ein Vergleich zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der DDR. Frankfurt 2002, p. 422.

Von der Lippe, Peter, 1977: “Asta Hampe 70 Jahre.” in: Allgemeines Statistisches Archiv 61, 1977, p. 211 f.

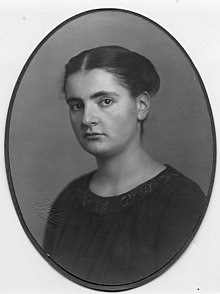

February: Margaretha Rothe

Margaretha Rothe

Margaretha Rothe studied medicine at Universität Hamburg and was a member of the Hamburg branch of the White Rose resistance group during the Nazi regime.

Born in 1919, Margaretha Rothe attended secondary school in Hamburg before commencing a degree in medicine at Universität Hamburg in 1939. Alongside her studies, Rothe and her friend and fellow medical student Traute Lafrenz took part in a reading circle established by the resistance fighter Erna Stahl. Rothe got to know fellow students and physicians critical of the Nazi regime with whom she formed discussion groups to debate cultural and political issues.

The Hamburg oppositional group was infiltrated by a Gestapo spy and in 1943, more than 30 people were arrested, among them Margaretha Rothe. She was accused of intent to commit high treason, aiding the enemy, undermining the military, listening to foreign radio broadcasts, and intent to commit a crime using explosives. She was held in prisons in Hamburg, Cottbus, and Leipzig.

Margaretha Rothe died in Leipzig on 15 April 1945, aged 26, as a result of the catastrophic conditions in the prisons where she was held. She was buried at the Leipzig Südfriedhof, but her remains were reinterred at the Ohlsdorf Cemetery in Hamburg after the war.

Opposition activities

Margaretha Rothe was both politically and socially active. To take a stand against the suppression of freedom of expression under the Nazis, she distributed leaflets, which she printed using a children’s printing kit, detailing the airing times and frequencies of foreign radio stations. The leaflets also criticized the Nazi regime and the war.

In 1941 Margaretha Rothe joined the group centered around Hans Leipelt and Reinhold Meyer, which later became known as the “Hamburg White Rose.” At secret meetings the students discussed banned literature, current political issues, and the military. Through their network of friends and acquaintances, the group was in contact with Hans and Sophie Scholl in Munich; and the now famous leaflets of the White Rose made their way to Hamburg.

Margaretha Rothe was an open-minded young woman and an ambitious student, whose actions during her studies at Universität Hamburg proved her humanity and courage. She appealed to her fellow citizens’ sense of responsibility, and stood up for civic engagement and an open society.

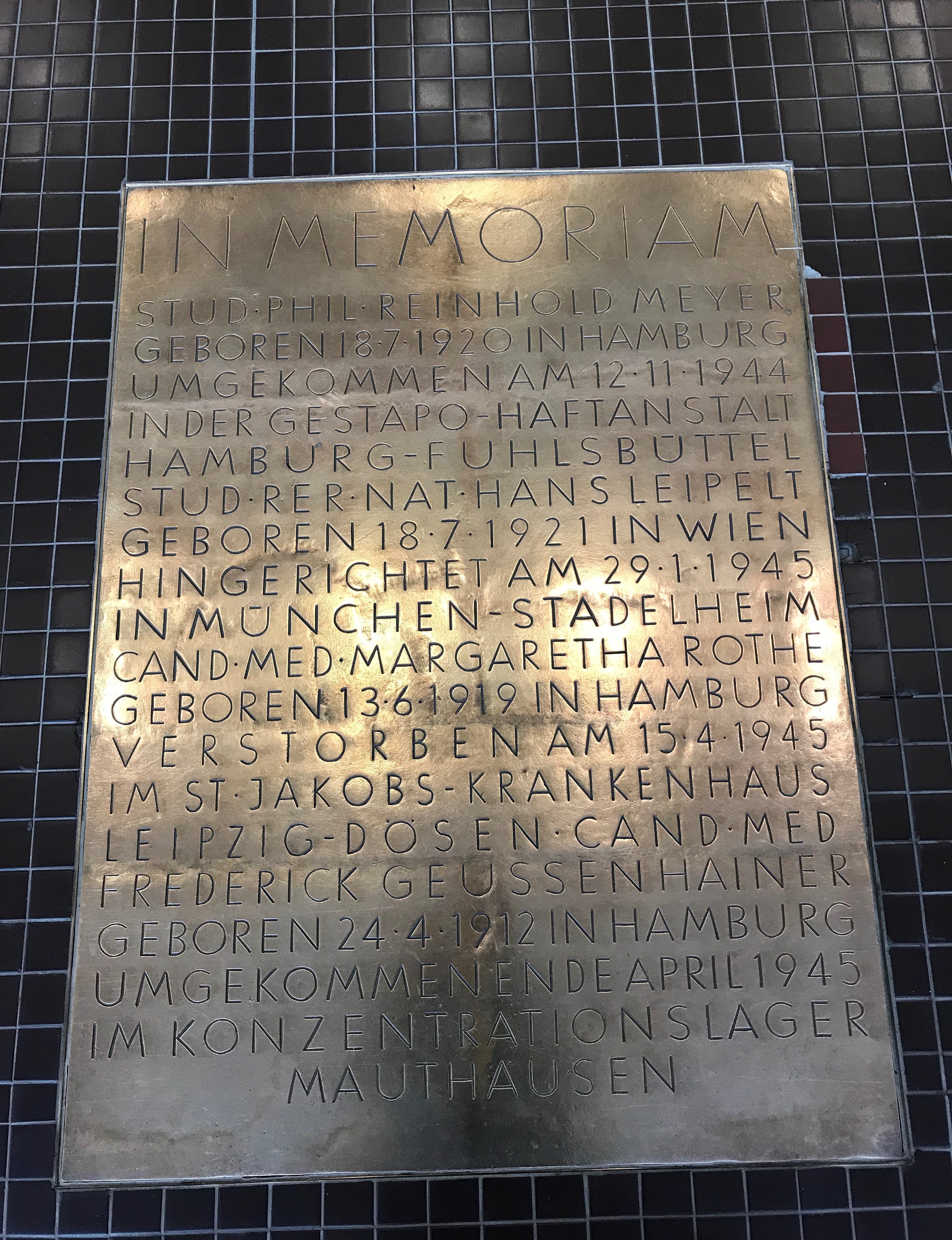

Memorials to Margaretha Rothe

Margaretha Rothe’s name is still to be found all over the city of Hamburg. A street in a northern suburb of Hamburg, Margaretha-Rothe-Weg, was named after her in 1982, as was a building on the grounds of the University Medical Center, the Geussenhainer-Rothe-Haus (1987) and a high school in Hamburg, the Margaretha-Rothe-Gymnasium (1988).

In 1984, a memorial plaque with the names of the Hamburg activists was placed on the former bookshop in the city center at Jungfernstieg (the Agentur des Rauhen Hauses) where they met in the cellar to discuss and plan their activities. A memorial stone was placed in her honor in the Garden of Women at the Ohlsdorf Cemetery. In addition, a total of four Stolpersteine (small brass “stumbling blocks” the size small paving stones—10 by 10 centimeters—in which are inscribed the name and life dates of victims of Nazi persecution and extermination) throughout Hamburg memorialize her contribution.

The former Cottbus Prison, where Margarethe Rothe was imprisoned, was transformed into a memorial site in 2013. It displays original documents such as letters and textbooks. The memorial “Table with 12 Chairs” stands in the Hamburg suburb of Niendorf. It represents the 12 Hamburg resistance fighters murdered by the Nazi regime.

Universität Hamburg and Margaretha Rothe

Universität Hamburg also offers a memorial to Margaretha Rothe. In 1971 a floor plaque was installed in the University's main auditorium to honor Rothe and her fellow student activists of the resistance. A student dormitory in the inner-city suburb of Winterhude also bears her name. On 1 December 2016 the then Paul-Sudek-Haus was ceremoniously renamed the Margaretha-Rothe-Haus. The renaming was initiated by residents, who sought to make a statement about democracy and diversity.

Further information

Stolpersteine in Hamburg and biographical information

Memorial sites in the Hamburg metropolitan area: Illustrated wall panels

Memorial sites in the Hamburg metropolitan area: Memorial

“Stadtteilgeschichten” website (“suburban (hi)stories”)

Literature:

Groschek, Iris: “Rothe, Margaretha,” in: Hamburgische Biografie Vol. 4 (Hamburg, 2008) pp. 294f.

Schneider, Nina: Hamburger Studenten und Die Weiße Rose: Widerstehen im Nationalsozialismus. Begleitheft zur Ausstellung der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky. (Hamburg, 2003).

Staudacher, Ingeborg / Staudacher, Gunther (eds.): Margaretha Rothe, eine Hamburger Studentin und Widerstandskämpferin. (Balingen, 2010).

Staudacher, Ingeborg: Margaretha Rothe: Opposition im Dritten Reich. (Balingen, 2003).

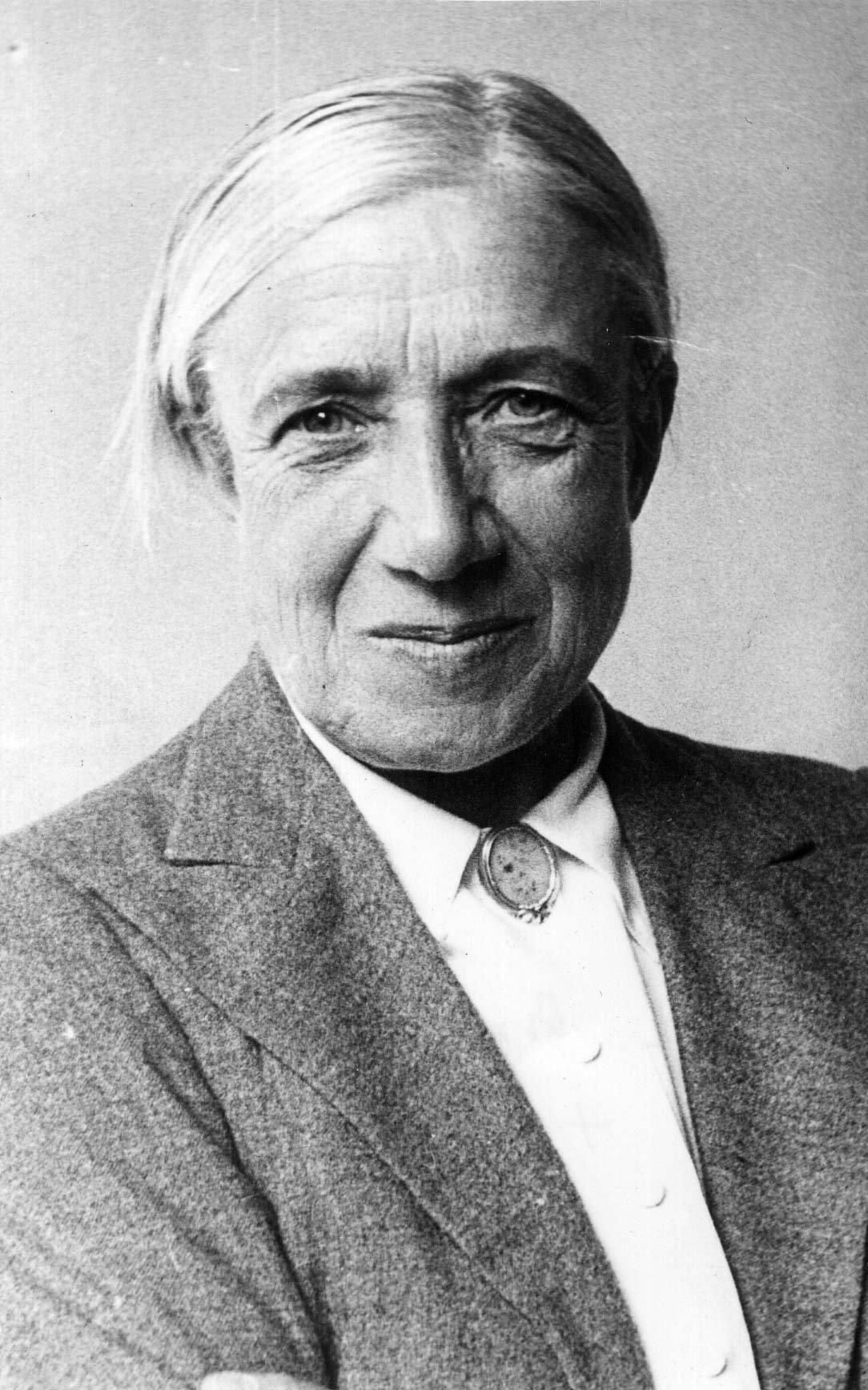

January: Magdalene Schoch

Magdalene Schoch

Image: Center for the History of Universität Hamburg

Magdalene Schoch was not only the first female legal scholar at Universität Hamburg to earn a Habilitation, the postdoctoral qualification that confers the right to lecture (venia legendi) in a particular subject at a German university: she was the first woman to do so in all of Germany.

Magdalene Schoch, born on 15 February 1897 in Würzburg, began her studies at the university there in 1916. She was one of the first women in Germany to study law. Schoch was also interested in literature, philosophy, and art history. Social and political issues were very important to her, and she was involved in student government. After 4 years of study, Magdalene Schoch was awarded a doctorate. She then followed her mentor, Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, to Universität Hamburg. Schoch quickly settled into life in the Hanseatic city, and was a highly influential figure in the University's development. Magdalene Schoch spent the second half of her life in the USA, where she emigrated in 1937 as a result of Nazi persecution in Germany. There she was able to use her knowledge to begin a new career. Upon her death in the USA on 6 November 1987, she was a remarkable woman who, throughout her life, had proven herself in a man’s world, and thus become a role model for women working in the law.

Research and teaching

In the 1920s Magdalene Schoch was instrumental in internationalizing Universität Hamburg's faculty of law and public administration and promoting international goodwill at the University and in the city of Hamburg. She worked not only as an assistant to Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, but also at the Institute for Foreign Policy, founded by Bartholdy in 1923. At that time, the Institute was one of the first in the world to study the conditions of peace, and was highly influential in the development of political science in Germany. Magdalene Schoch was named director of the Institute's law department in 1932. Due to the efforts of Magdalene Schoch and Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Universität Hamburg was the first German university to teach English and US American law.

Magdalene Schoch was one of the founding members of the Society of Friends of the United States—along with Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Kurt Sieveking, Erich M. Warburg, and Otto Laeisz—and served on its board. She edited the Society’s bilingual publication, the Hamburg-Amerika-Post, subtitled “A Messenger of good will between the United States and Germany.” In 1930 she was also appointed head of the new America Library housed in the University's new law building.

In November 1932 she submitted her Habilitation thesis on international private and procedural law, comparative law, and civil procedure, thus becoming the first woman in Germany to earn the postdoctoral qualification conferring the right to lecture at a German university in the discipline of law.

When her academic career was abruptly ended by the Nazi regime, she emigrated to the USA, where she started her career. After a period of working in a poorly paid position as a research assistant at the Harvard Law School, she was hired as an expert for German law by the Office of Economic Welfare, and later worked for the Foreign Economic Administration. She then worked for the US Department of Justice as an expert for international and foreign law, eventually becoming head of the division. Until her death she remained active as a consultant and attorney.

Commitment to social issues

In addition to her academic and professional activities, Magdalene Schoch was also committed to social issues. Her mother had been an early champion of women’s rights, and Magdalena followed in her footsteps. During her time at university, she had many friends who were Jewish or members of the German Social Democratic Party and she participated in numerous demonstrations. Later on she was one of the initiators of the Hamburg women’s front against National Socialism, and became the first president of the first German branch of the Zonta Club (an international organization dedicated to networking working women across nations), founded 1931 in Hamburg. Magdalene Schoch’s life was upended when the Nazis came to power. After usurping power in 1933, the Nazi regime rolled out its system of totalitarian control over all facets of German society (known in Nazi terminology as “Gleichschaltung”), including the universities. After Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy was dismissed from the Universität Hamburg in 1934 because of his Jewish heritage, Schoch’s standing in the law faculty became increasingly fraught. One after another, the projects she had worked on were destroyed by the Nazis: the Institute for Foreign Policy became an instrument of propaganda, the Hamburg-Amerika-Post was shut down, the Society for Friends of the United States was dissolved, and the Zonta Club was forced to disband, leaving its members no choice but to meet in secret. When all employees at Universität Hamburg were ordered to join the Nazi Party, Magdalene Schoch refused. She resigned in the summer of 1937 and emigrated to the USA in October. In 1946, as president of the Zonta Club in Arlington, Virgina, she organized an extensive program for collecting and sending care packages to Hamburg.

Universität Hamburg and Magdalene Schoch