Not a phenomenon of modernityWomen as Burglars, Fraudsters, and Thugs

19 March 2024, by Christina Krätzig

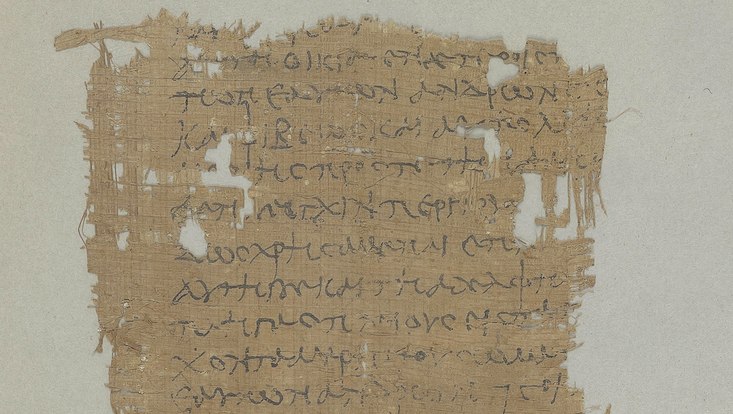

Photo: State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky (p.hamb.graec.144)

Each year, as part of the Agathe Lasch Visiting Scientist Program for Women in Academia, Universität Hamburg invites female academics to participate in a research stay of up to 6 months. Kerstin Droß-Krüpe, specialist in ancient history, is currently in Hamburg researching violent women in Roman-ruled Egypt.

Robbery, fraud, assault—what crimes did women commit during the Roman Empire, and why did they become perpetrators? To answer these questions, we must understand the economic, societal, and legal situation of women 2,000 thousand years ago and thus go beyond the traditional approaches, which strongly focus on literary sources. This is because literary texts reflect primarily the lives of the upper classes—as well as a male, literary, and idealized view of women.

“The documentary sources that can provide a more realistic explanation have received far less attention so far,” says Dr. Kerstin Droß-Krüpe, a Privatdozent (senior lecturer without a permanent teaching contract) of ancient history at the University of Kassel and a research associate at Ruhr University Bochum. For her current research project, Droß-Krüpe is collecting and analyzing petitions, letters, receipts, contracts, and lists from ancient Egypt that are up to 2,000 years old.

At that time, Egypt was a Roman province and already had a long tradition of writing—after all, writing on papyrus was invented there. Due to the hot and dry climate in the region, many of the fragile documents have survived. “They offer fascinating insights into the everyday lives of people in antiquity, also beyond those of the upper classes,” explains the historian, who is able to focus entirely on her current research topic for 6 months thanks to the Agathe Lasch Visiting Scientist Program for Women. “Using papyrus documents, we learn—for example—that women worked as timber merchants and dyers; however, that is not mentioned in antiquity dramas or Roman historiography. In the papyri, we also read about how poor large parts of the population were. For many, securing subsistence and paying taxes was a near-impossible task.”

Droß-Krüpe is using the time in Hamburg to examine the preserved and published material. During this process, she is concentrating primarily on so-called petitions—that is, letters from victims who wish to report a crime to the Roman magistrates. “Be it assault, coercion, defamation or criminal damage, robbery, theft or fraud or embezzlement, women were accused of all imaginable crimes,” says Droß-Krüpe. In most cases, however, she is unable to follow up on whether all these crimes were actually committed, whether they made it to court, and what sentence was handed down to the perpetrator. What is important, though, is that “The letters show that it was absolutely conceivable in the mindscape of people in Roman Egypt that women could have committed such crimes.”

This is interesting against the background of increasing female violence in the present.

In Germany, there have never been more girls who commit acts of violence against other girls. And during the coronavirus lockdowns, even mothers made the headlines for being violent toward their children or partners. “This phenomenon has been the subject of both media coverage and academic studies,” explains Droß-Krüpe. According to the historian, however, explanations based on changes in modern role models come up short. After all, the analysis of historical documents shows that women as perpetrators is by no means a modern phenomenon.

In the summer semester, her passion for papyri will be incorporated into a course at Universität Hamburg. Together with Prof. Dr. Kaja Harter-Uibopuu of the Ancient History working group and the Cluster of Excellence Understanding Written Artefacts, Droß-Krüpe will teach a seminar on the areas of employment and activity of women in antiquity, in which the focus will be on papyri and inscriptions.

Agathe Lasch Visiting Scientist Program for Women in Academia

As the first female Germanist in Germany, Agathe Lasch received the title of professor from Universität Hamburg in 1923. Named in her honor, the interfaculty funding program aims to support women in fields in which they are underrepresented. Visiting professorships are open to female professors or researchers with a Habilitation or equivalent (e.g., junior professors, associate professors) from Germany or abroad.