International neuroscience researchCan People Born Blind Learn to See?Doing the Research series

4 December 2024, by Anna Priebe

Photo: Sebastian Engels

Our brain can adapt to changing conditions throughout life, but some processes are only possible in the developing brain. Within a German-Indian collaborative project, Prof. Dr. Brigitte Röder, a professor of Biological Psychology and Neuropsychology, investigates whether people born blind can learn to see after sight-restoring surgery later in life and which neural processes support or interfere with sight recovery.

You are investigating human brain development. What is your focus here?

Through our work, we want to find out how experience influences human brain development. We use vision and neural systems associated with vision as a model.

So you are investigating how the brain of a person born blind is developing compared to the brain of a sighted person?

We are particularly interested in the question of whether the brain of a person born blind, who has adapted to blindness from an early age, is capable of reorganizing later in life to process visual input after sight restoring surgery. Thus, we aim to understand what is known in psychology and neuroscience as sensitive periods in human brain development.

What did you discover?

We were able to demonstrate that after surgery, visual information reaches the so-called primary visual cortex, the earliest stage of visual cortical processing, as quickly as in sighted people— regardless of age at the time of the surgery. By contrast, the subsequent processing in higher-order brain areas, remains impaired in these sight recovery individuals. This explains why these individuals are able, for example, to distinguish a face from other objects, but have difficulties in recognizing individual faces.

What methods do you use?

We mainly use the electroencephalography, or EEG for short. This method can be easily used in people of all ages without causing a significant burden for the participant. Participants wear a cap with embedded electrodes that touch the scalp. These electrodes are able to pick up the subtle electrical brain activity. From these measurement signals can be extracted that allow us to trace individual stages of visual processing pathway.

Additionally, we employ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI enables us to assess the structure of the brain in addition to its function. We are particularly interested in visual areas. Paradoxically, like others before us, we found that the visual cortex is thicker in people born blind than in sighted people. This result was interpreted as a lack of developmental shaping of visual brain areas in blind people, which includes the pruning of excess connections. Our studies show that this structural remodeling of visual areas depends on vision after birth and does not take place if sight is restored later in life.

What can we conclude from the results?

Our studies demonstrate that early childhood experience defines structural brain development and that the lack of adequate early experience cannot be remediated later in life. Most likely, this principle holds true for other parts of the brain that are associated with functions such as language, behavioral control, or socioemotional development.

If structural brain development limits functional brain development, it follows that missing adequate input or unfavorable environments must be prevented or remedied as early as possible. Our future research will address therapeutic measures capable of targeting the remaining plasticity of the brain at any given age. For example, gamified perceptual learning settings could be useful.

The very specific characteristics of the research participants qualifying for your studies pose a challenge for your research, right?

As very good medical care is available in most Western countries, we rarely see people who have treatable blindness but have not received treatment for years. We examine people whose blindness was caused by congenital cataracts. Most of us know cataracts as opaque lenses of the eyes in older age. Congenital cataracts often have genetic causes or develop during pregnancy. In Western countries, they are usually detected in routine examinations shortly after birth and operated on within the first few months of life.

You have therefore been working with the L V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI) in India for more than 10 years. What makes this research collaboration special?

Affordable eye care cannot be taken for granted in all regions of India, especially not in rural regions. The LVPEI has established a network for eye care in four states of South India. Thanks to its own revenues and in part to donations, the institute is able to offer 50% of treatments free of charge, so children and adults get access to treatment regardless of their financial situation. Additionally, LVPEI is one of the world’s leading research institutes in the field of ophthalmology.

We have greatly benefited from the research infrastructure of the LVPEI and were able to set up a lab in Hyderabad that offers similar research methods as our labs in Hamburg, including EEG. Working together with the L V Prasad Eye Institute is a unique opportunity for us, without which our research would hardly be possible.

How do you recruit the research participants?

The Indian colleagues recruit the patients; they explain the study to eligible patients and in case of minors, their parents. The patients will only be invited to our laboratory once they or their legal guardians have given consent. It is clearly communicated from the outset that participation in our research is completely voluntary and independent of treatment at the LVPEI.

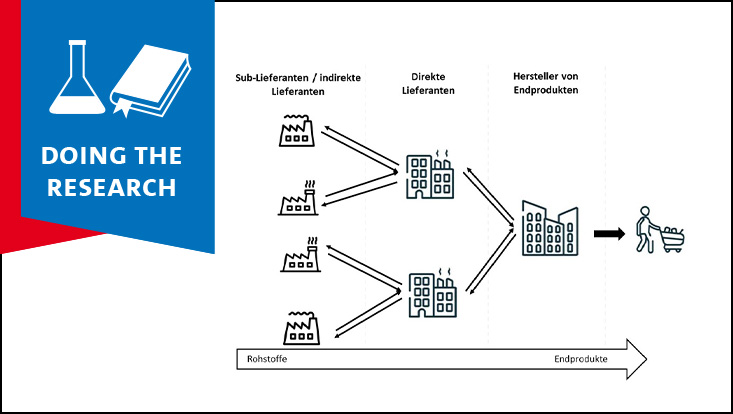

Doing the Research

There are approximately 6,200 academics conducting research at 8 faculties at the University of Hamburg. Many students also often apply their newly acquired knowledge to research practice while still completing their studies. The Doing the Research series outlines the broad and diverse range of the research landscape, and provides a more detailed introduction of individual projects. Feel free to send any questions and suggestions to the Newsroom editorial office.