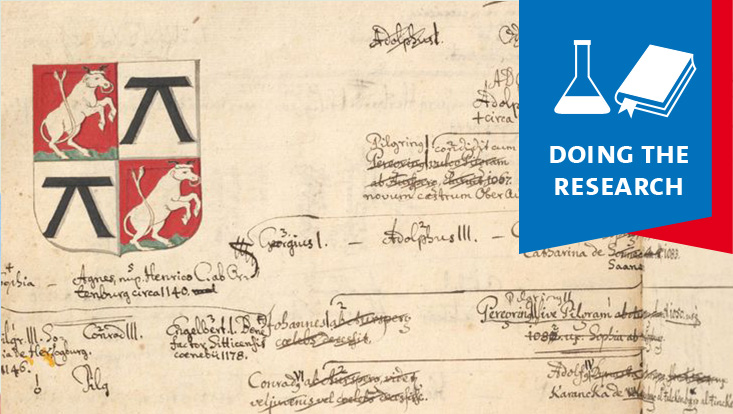

Genealogy ResearchThe Power of Ancestry in Early Modern Asia, Europe, and Middle EastDoing the Research series

14 November 2023, by Viola Griehl

Photo: Markus Friedrich

Social, political, or religious privileges are often derived from imaginary or real lineages. Researchers are now scrutinizing the role of ancestry in different cultures and epochs in the World Genealogy project. The 4 projects, of which 3 are being led at Universität Hamburg, are being funded by the German Research Foundation in the amount of €1.23 million.

Prof. Markus Friedrich, you are looking at the most important reference work on European nobility, the Almanach de Gotha. What exactly interests you as a researcher?

The Gotha is an annually published directory of the German nobility and it includes the most important noble families in Europe and the world. Despite several breaks due to upheavals in the twentieth century, it remains available with a few changes.

The Justus Perthes publishing house in Gotha earned off this reference work for decades because it sold so well. And historians have used the Gotha again and again as a reliable reference work, without, however, really looking into how the Gotha actually emerged: how was an updated handbook created year by year and how did this guide to nobility change throughout time?

It is also illuminating to see how individual noble families have reacted to the guide—some were very satisfied with how they were portrayed, others not at all and they have tried for years to achieve what they see as a better portrayal. All of this shows how enormously important genealogy—more precisely, the right portrayal of one’s own genealogy—was for nobility, but also for the public.

Prof. Barend ter Haar, in your project you are looking at genealogy in late Imperial China. What is the focus of your investigations?

Our project focuses on the Huizhou region and looks at how genealogies were used to create large family alliances. Huizhou has been known as a center of neo-Confucian studies since the eleventh century and is famous for its merchants, among other things, especially during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1645–1911) Dynasties.

Mercantile wealth in Huizhou rested on cleverly arranged family alliances. These formed powerful social communities whose members were bound together based on (alleged) common ancestry and relatives. The alliances were created both through genealogy and through Confucian rituals or via close links between these two practices. The transmission of knowledge about ancestry and the shared ritual of commemorating ancestors created a shared identity for everyone involved. The social groups or family alliances that arose as a result had a two-fold purpose: on the one hand, they facilitated competition with other, similarly arranged ancestral groups and village communities, and on the other hand, the negotiations with the state with regard to questions of local authority, tax privileges, and social status in the various historical epochs. In these processes, the deeper meaning of genealogy as a form of cultural capital becomes clear because it strengthened local groups in their interactions with the state and its local representatives.

Prof. Steffen Döll, you are looking at the connections between genealogical records in Zen Buddhism and religious authority in Early Modern Japan. What are you focusing on concretely?

In Zen Buddhism, the question of ancestry plays a very central role. Genealogy, however, is understood in a very special way because it’s not about biological but about spiritual ancestry.

The fundamental idea is that the Buddha, in addition to all the teachings available in writing, also and above all handed down something that escapes every conceivable linguistic formulation. This “handing down from heart-to-heart” is supposed to have occurred between Buddha and his pupil Mahākaśyapa, who thereby became his successor. In the next generation, Ānanda followed and after him, the succeeding generations. Representatives of Zen Buddhism thus assume that they are part of an unbroken tradition that goes back over 2,500 years. This belief is documented in genealogical diagrams that are still being created, continued, or changed today and are handed down through history in many variations.

Our project goal is to trace these genealogical diagrams, from the Middle Ages to Modernity, in their development and authorship, circulation, and transmission as well as their respective references to other diagrams. We are basically interested in a genealogy of genealogies because that allows for an understanding of legitimation strategies with regard to teachers and pupils, to the power claims of Zen Buddhist institutions, and to the external reception of the knowledge contained in the diagrams.

Project information

World Genealogy. Presenting, Documenting, and Instrumentalizing Lineages in Early Modern Asia, Europe, and the Middle East is a “package” of 4 projects to receive funding from the German Research Foundation. The funding covers, in addition to the 3 projects at Universität Hamburg headed by Friedrich, ter Haar, and Döll, the project Dynastic Genealogical Trees in the Early Modern Period: Visualizing Historical Imagination and Political Legitimacy in the Islamic World headed by Dr. Evrim Binbaş from the Department of Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Languages at the University of Bonn. All 4 projects are their own independent endeavors but principle investigators and research staff will work closely together and compare findings and questions in frequent work sessions. The researchers are also cooperating with the Early Modern World core research area and the Cluster of Excellence Understanding Written Artefacts at Universität Hamburg. The entire venture started on 12 October in conjunction with the GIGA-coordinated lecture by Dr. Nadav Samin (Washington, DC): “Genealogy from Islamic History to Modern Saudi Arabia.”