Baltic Health IndexThe health of the Baltic Sea is below standard – but there’s hope for improvement

26 March 2021, by Fintan Burke

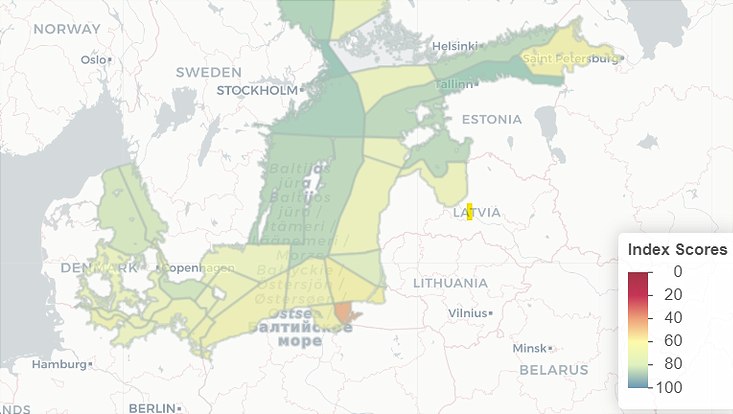

Photo: Baltic Health Index Project & OpenStreetMap contributors

An international research team with participation of Universität Hamburg has developed an index that can be used to assess the condition of the Baltic Sea. But how does this "Baltic Health Index" (BHI) work? And which grade does the Baltic Sea currently achieve?

Researchers assessing the health of oceans used to involve simply examining the components of an ecosystem without asking what value these components bring to society.

But in recent years oceanographers have begun to examine the status of oceans by asking what ecosystem sectors are affected by people, and what ecosystem sectors do people most value. Examining this human-nature interaction is important when designing modern ocean resource management policies (e.g. Policies for ocean conservation, food production, and recreation). It led to the first Ocean Health Index (OHI) performed by US researchers in 2012.

Now a similar survey focusing on the Baltic Sea shows that its ecosystem needs to improve drastically. The study has been published in the journal People and Nature and is available to view on it’s own website.

Prof. Dr. Christian Möllmann from the Institute of Marine Ecosystem and Fisheries Science at the University of Hamburg examined the health of the Baltic Sea’s fish stocks in the study.

He notes that one of the unique aspects of the study was including the human element of the study, to make it more holistic. “The idea was to make an assessment that covers all the sectors and also the social ecological linkages,” he said.

Using the OHI as a framework, the paper’s authors used regularly updated environmental, ecological and social datasets to assess the health of the Baltic Sea. These datasets included information on water cleanliness, biodiversity and tourism, for example. Prof. Möllmann focused on the ‘sustainable fishing’ sector; this involved checking if the amount of fish species caught exceeded the threshold that is considered sustainable.

“Basically, the whole index is a data collection exercise. And then you have to make decisions on what the thresholds are,” he said.

The resulting index unfortunately shows partly an unhealthy relationship between ecosystems and social systems of the Baltic Sea. The Baltic Sea overall scored a 76/100 in terms of health. The worst performing sectors were water contamination, excess algae and plant matter (eurtophication) and the sea’s ability to store carbon.

The results are mixed, though there’s been some small improvements. For example, the Bothnian Bay and Kiel Bay scored high in water quality. However, the stocks of cod, which Prof Möllmann studied scored low for the entire Baltic Sea region. Nearly all the areas nevertheless also showed signs of improvement, pointing to a healthier Baltic Sea in the next few years.

“In the end, it shows that [the Baltic Sea] is maybe better than expected, but there's still room for improvement,” said Prof. Möllmann.

While it is not perfect, Prof. Möllmann says the BHI provides policymakers and oceanographers a way to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of how the Baltic Sea is managed. The next steps for the authors are to improve the assessment by updating its methodology and adding new data, said Prof. Möllmann.

For now Prof. Möllmann is using the data from the index for the “balt_ADAPT” project, which is developing a climate change adaptation strategy for the Baltic Sea region.

“We want to link the work from the index project to our project, so that we can make better estimates for the western Baltic,” he said.

Original publication

Blenckner, Thorsten, et al. "The Baltic Health Index (BHI): Assessing the social–ecological status of the Baltic Sea." People and Nature (2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10178