Offers for early career researchersTenure Track: A Bit More Certainty

21 February 2024, by Anna Priebe

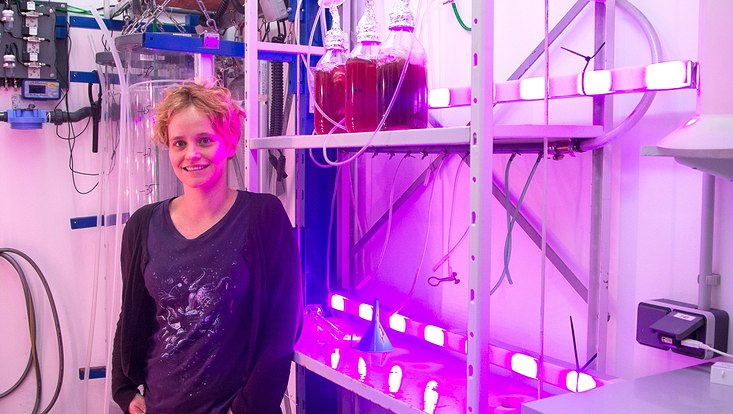

Photo: Universität Hamburg / Wohlfahrt

From April, Dr. Elisa Schaum will be a W2 professor of plankton ecology and evolution at Universität Hamburg, having successfully completed the the tenure-tenure-track procedure after 6 years as a junior professor. In this interview, Schaum talks to us about how she benefited from the program and what’s to come.

Congratulations on successfully completing your tenure-track program. How did you celebrate?

Big celebrations aren’t really my thing or—having a young daughter—really an option. Also, I had a few application deadlines for research funding programs. But that evening, I had a friend over for dinner and shared the good news with her, and I visited another friend in Scotland a few days later—where we celebrated a bit.

The decision was made after 6 years. What is the program like?

There are 2 evaluations in total: An interim evaluation after 3 years and a final evaluation after 6 years.

The interim evaluation looks at whether research and teaching are heading in the right direction. You write, for example, a summary about acquired external funding, what you have done in teaching and research, and what you have in mind for the future. On the basis of that evaluation, tasks are adapted and even new goals are set for up to the final evaluation. For instance, I received the feedback that I should shift my focus between research and teaching a bit more toward research. This balancing is not always so easy.

Among other things, the final evaluation looked at the extent to which the steps discussed had been implemented. You also present your research topic and are required to give a short lecture on an assigned topic. Of course, there are also talks with department representatives.

So does that also mean that you already had guidelines when you started the program?

They always look at each person individually.

There is an agreement on activities and goals at the start. Each person is always looked at individually. In my field of research, for example, there was previously no tenure-track professorship. That meant there was no experience with guidelines.

But that made it variable. The guidelines you need depending on the type of experiments you conduct. Some experiments produce findings after 2 weeks, but I conduct long-term experiments, for which you first get results after a couple of years. That will be taken into account, for example, in terms of the expected number of scientific publications.

I found it helpful in other contexts that the program could be tailored. For instance, expeditions were not possible during the pandemic, which had a direct impact on my research. Also, the birth of my daughter changed the situation so much that I sought out the talk. The evaluation was then moved.

Based on your start in 2017, what advantages does the tenure-track program offer early career researchers?

For me, it’s an advantage that you have a bit more certainty due to being able to stay where you are. Junior professors without tenure track often have to leave the University after 6 years. Due to the academic fixed-term labor contract act (Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz), you don’t really have the chance to work in academia permanently. In that respect, the program represents an important and positive step. But it can’t remain the only way to give early career researchers a chance.

How have you benefited from the program’s content?

The evaluations are extra work, but they are extremely valuable because you receive feedback and can see where there is room for improvement. What also helped me was the informal mentoring by 2 senior researchers from my department, whom I was able to ask questions. Neither had done tenure track, but they were both able to support me with many matters. There are also various official mentoring services offered by the University.

You research the impact of climate change on phytoplankton. What findings have you made in the 6 years since your inaugural interview?

Up to that point, I had focused primarily on abiotic factors, such as carbon content and water temperature. Now, however, it has become increasingly apparent how important biotic interactions between phytoplankton are—namely, how marine viruses can change the features of phytoplankton. It’s long known that these viruses exist; however, their impact on the ecological functions of phytoplankton has seldom been explicitly researched in the laboratory.

Do you already have specific projects or expeditions lined for your new role as professor of plankton ecology and evolution at Universität Hamburg.

In the coming 3 summers, we will be going to Qeqertarsuaq, Greenland, in the far north. There, we will focus on polar phytoplankton species and, in particular, how likely it is that they could be displaced by other species. That is a big project, which will be funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. I’m really excited as I’ve never been that far north before.

Moreover, we will focus in depth on the fluctuating environmental conditions—for example, heat waves and their impacts—because many of the answers that microbacterial organisms have for environmental change are highly dependent on what kind of changes they have already experienced.

In the Baltic Sea, we researched 2 adjacent areas that are separated by only a couple of hours by ship. The conditions of one of the basins fluctuated very erratically; the other basin was more protected and thus had more predictable fluctuations. One type of phytoplankton found in both basins reacted very differently to environmental changes in experiments—dependent on which basin they came from. We want to extend this knowledge to other areas since it would be quite handy if we could use long-term monitoring data from an area to see how the environmental conditions fluctuate there and how phytoplankton species are likely to develop under certain changes.

About

Prof. Dr. Elisa Schaum has been a researcher in the Department of Biology at Universität Hamburg since 2017. Up to now, she has been a junior professor at the Institute for Hydrobiology and Fisheries Science. As of April 2024, following her successful completion of the tenure-track procedure, Schaum will take up the position of W2 professor of plankton ecology and evolution. Prof. Schaum researches and teaches biological oceanography and, in particular, the impacts of climate change. Schaum is a member of Cluster of Excellence Climate, Climatic Change, and Society (CLICCS) and the Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN) at Universität Hamburg.

The tenure-track program

With its tenure-track program, Universität Hamburg—University of Excellence offers outstanding early career researchers more certainty when planning their career paths and ties them to the University for the long term. Whereas junior professorships last 6 years at most and end with the early career researchers departing for another university, the tenure-track program entails another evaluation after 6 years. If the evaluation is successful, the junior professor receives a full professorship without a call for applications or an academic search procedure. Find more information on the Professorial Appointments Unit’s website.