PS: It is warStudent research project on letters to and from the front

27 November 2017, by Anna Priebe

How does love function in war? To find this out, 10 students examined a trove of letters between a husband at the front and his wife at home during the First World War. The student-led seminar project earned its organizers more than just credit points.

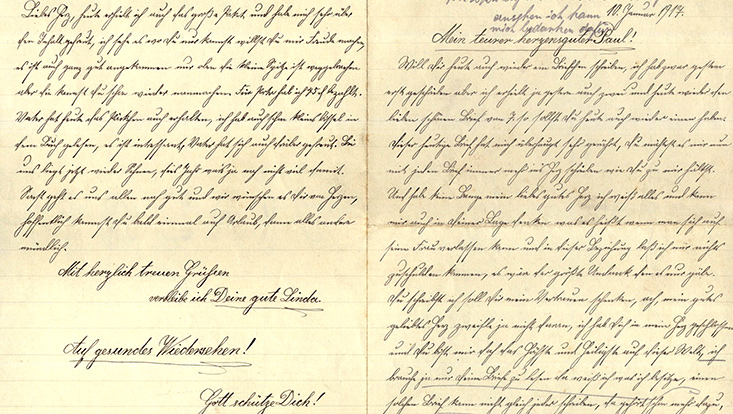

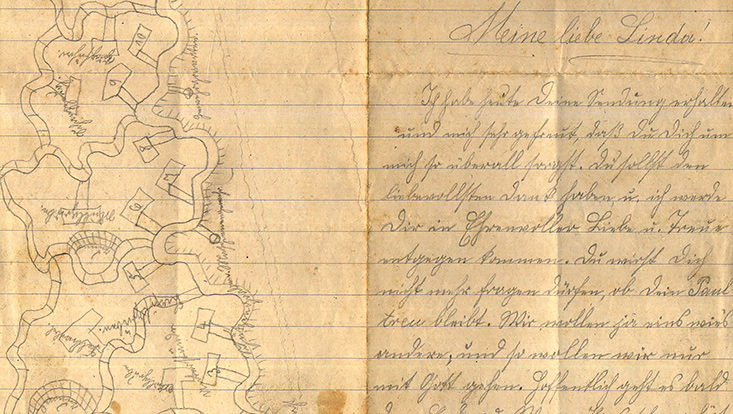

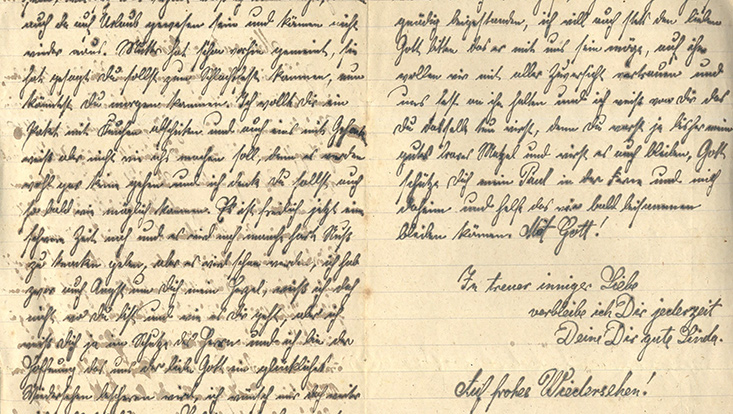

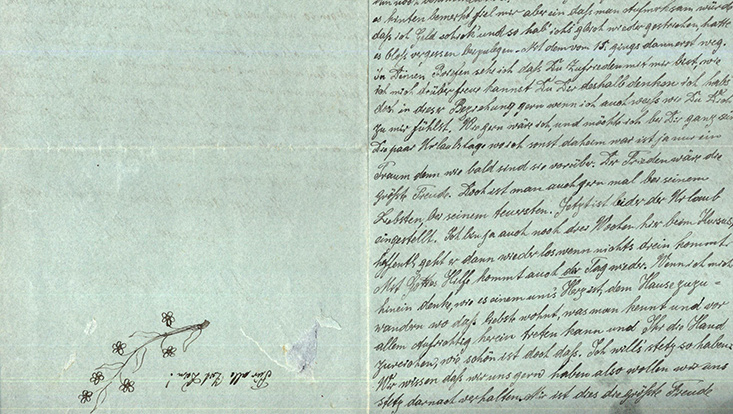

“Dearest Paul,” Linda Trompelt begins her letter on 19 January 1917. She writes to her husband at the French front to tell him that he is her “dearest” and that she will send him a parcel of fat the following day that he should please not eat if already rancid upon arrival. For Ronja Ewert this letter is special: “Paul corrected the letter and, using a colored pencil, inserted commas everywhere.” Even though, as Tabea Henn adds, “his spelling and punctuation were much worse than hers.” Together with 7 other students under the aegis of Désirée Kaiser, Ewert and Henn collated an annotated edition of more than 150 front letters that the couple wrote to each other between January 1915 and November 1918.

For historians, compiling an “annotated edition” entails deciphering the letters, typing them up, and providing explanatory comments for the reader according to predetermined criteria. The result of this project is a some 400-page book containing the edited and annotated correspondence as well as an essay by each student involved in the project on a particular research question. Désirée Kaiser discovered the collection of letters during her research and purchased them privately from a militaria dealer. Kaiser, now a doctoral candidate, offered the research project during her master’s degree as a seminar in the Faculty of Humanities in 2016. “Our overriding topic was the question of how intimate relationships during war function through the medium of the letter and to what extent concepts of “the couple” are shored up through these letters: in effect a gender-theoretical approach.”

On the one hand, women were expected to strengthen the morale of their husbands-in-combat through letters from home; instructions and presentations taught women how to write good letters to the front. On the other, these letters provided the only means for couples such as Paul and Linda to keep in contact. “We see how the authors place the relationship over language, how couples attempt intimacy, and how the letters bring forth clandestine meeting points,” explains Kaiser. The concept of a “relationship” was, however, very different to the one we have today. “Especially in that past society where the man had the say, the letter also serves to sustain this hierarchy,” explains Kaiser, who researches in literature. And so Linda directs questions about new purchases to her husband who, according to Kaiser, “organizes the day-to-day at home from the front.”

“You know that I have long wanted a [wardrobe] and now sometimes there are some cheap ones, I think 50 Mark would buy a really lovely one, but that can wait until you come home, I just want to write to you of it.”

Lines like this posed an even greater challenge to the students: “As there was a lot of censorship, the letters were actually unbelievably low on content. It’s always phrases like: ‘I am faithful to you,’ ‘I am yours forever,’ ‘I love you,’” says Ewert, whose essay explores the importance of religion for the Trompelt couple. “But that just spurred us on to hone our perspective,” Kaiser adds. This triviality, she maintains, is in itself worthy of investigation, “when one takes into account the conditions under which these letters were written.”

At the outset, the students knew little more of the couple than that their first names were Linda and Paul. Later on they discovered that “home” was in Saxony and, by sheer accident, Paul’s last name. Armed with this information, history student Tabea Henn consulted the registry of births, marriages, and deaths responsible for the Trompelt’s district today—with success. She found out Paul’s and Linda’s full names, when they married, that they had had a daughter who died in 2015 and whose estate was the source of the letters. “At one stage I began to really shiver with excitement,” Henn remembers.

And into the bargain, she chanced upon a picture of the Trompelts from 1916 in one of the daughter’s publications. “That really was a stroke of unbelievably good luck, as prior to that we hardly knew anything about them; we didn’t even know if Paul had survived the war,” the 21-year-old says with excitement. All of a sudden they had faces to go with the words in the letters. Using this new information, Henn traced Paul’s stations on the front.

“And Linda last night you lay next to me as if I was home I [wanted] to embrace my sweet heart [but] there I held the wall and the dream was passed.”

“Those are the moments that you feel with your subjects,” Henn confesses. “At one stage I was a little sad about the fact that they will never know that they have made it into the history books, that their letters have such great importance for the world.” For Kaiser it was precisely this connection to the couple that proved the motivation: “I felt a little like I owed it to both of them to turn out a really good publication.” Paul and Linda, Kaiser explains, are 2 voices out of millions, the letters 150 out of billions, and “we have brought these two figures back to life to stand in for all those others.”

“Greetings from the deepest place in my heart from your good and grateful Linda”

This text appears in the current issue of 19NEUNZEHN, the student magazine available in all foyers, cafeterias, and libraries across the University.